Despite his lack of creativity, Stan Lee did bring assets to the table that helped Marvel become a cultural icon. Had he been content showcasing those talents and not overreaching for credits he did not deserve; his legacy could have remained largely controversy-free. Whether it was simply a reflection of his own charismatic, glad-handing personality or an honest-to goodness flash of insightful intuition, the snappy, slangy, and energetic dialogue he produced for both comic stories and letter columns was a breath of fresh air compared to the stilted and stoic language employed in other competing journals (Riesman, 2021). It is hard to claim that the sense of fun and liveliness Lee brought to his comic’s verbiage, didn’t make a big difference on their impact with fans. Some believe that this penchant for “wisecracks, asides, and colorful turns of phrase” were a necessary counterpoint to Kirby and his serious storytelling. Although not an opinion shared by all, Kirby’s dialogue in the New Gods series “were disappointingly flat. The stories and art continued in the same grandiose, heroic, mythic vein but the sense of fun and humor that had characterized his best work with Lee was absent” (Cwiklik, 1995). This point does need to be taken with a grain of salt, however, since what is considered a “sense of fun and humor” to some fans, however, was viewed as cheesy and distracting to others.

Despite tense relationships with the earliest of Marvel’s creative talent, like Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko, later additions to the bullpen were largely complimentary and appreciative of the informal and friendly atmosphere Lee maintained at the office (Riesman, 2021). He is almost invariably described as a likeable guy, sincere in his attention, and perpetually upbeat. Artist Vince Fago recalled: “Everybody felt Stan was wonderful. He kept things pretty loose.” Jim Salicrup adds:

[Stan] had a very dynamic personality, he was always on the go, he was always working hard. There was a friendly vibe in the bullpen in that, even though he was clearly the boss, he was Stan. Everyone was on a first-name basis. He would go out of his way, just like if he was at a convention, to treat everyone as well as he possibly could … People could look at it as being manipulative, but he had to make the people working with him be as happy to do it–to enjoy it as much as he was enjoying it–as possible (Riesman, 2021).

Lee clearly had a vested interest in keeping the Marvel bullpen happy and productive but, in comparison with the working atmosphere at competitor offices, that cynicism could seemingly be overlooked.

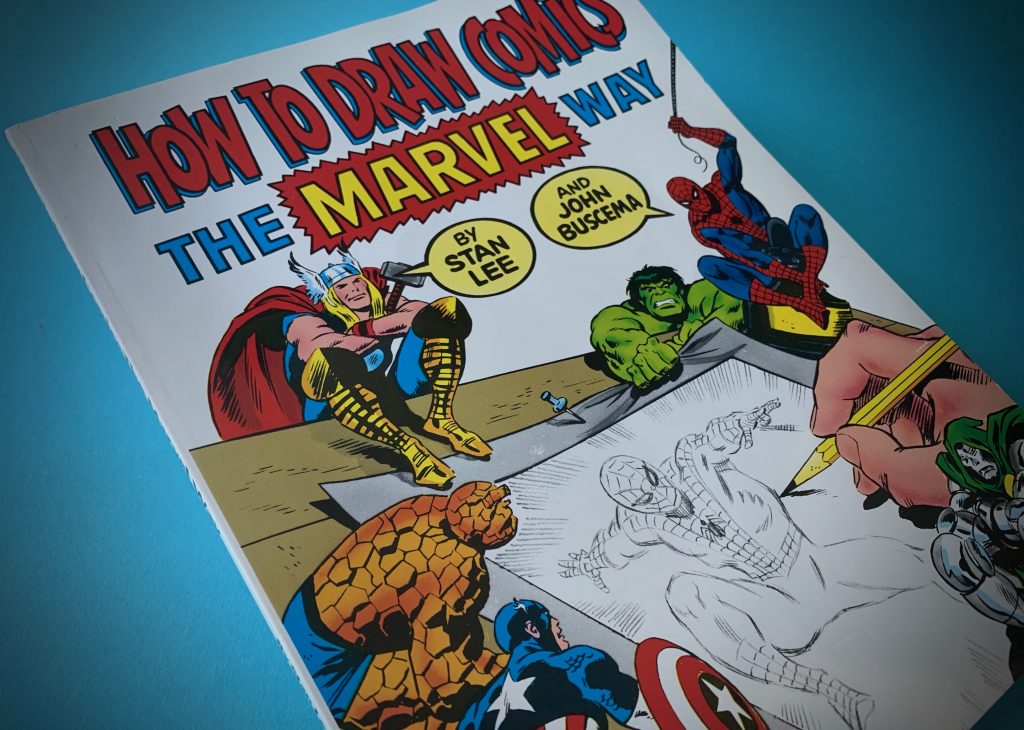

There were rare-exception Stan Lee projects that did see the light of day and were moderately successful. Upon close examination, however, they invariably had a connection to the industry Lee was forever trying to break away from: comic books. In 1947, Lee wrote a cover story for Writer’s Digest entitled There’s Money in Comics. That same year, he self-published the book Secrets Behind the Comics (Morrow, 2019). 1974 saw the publication of Stan’s book Origin of Marvel Comics. It was popular enough to warrant two sequels (Scioli, 2020). A graphic-novel adaptation of Lee’s Amazing Fantastic Incredible: A Marvelous Memoir was one of the few mild-success stories of the POW! days (Riesman, 2021). As a comics-obsessed kid who also liked to draw, one of my favorite books was Lee’s How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way (Lee, 1978). I knew nothing about the potential controversy, of course, but can’t help but wince now that I’m aware of the backstory. As Gregory Cwiklik points out: “That is why How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way is such an absurdity–it substitutes style with substance. Artists have been copying Kirby for the last thirty years, but they have never been able to replicate his inventiveness or imagination” (Cwiklik, 1995). Although Lee partnered with John Buscema on the book, it was full of Kirby art. As Riesman accurately points out, the “Marvel Way” was pretty much the “Kirby Way” (Riesman, 2021). The fact that success only seemed to come when Stan Lee was regurgitating (or fabricating) comic industry lore bespeaks a difficulty with producing content that was truly original.

Although they seem to be efforts at self-deprecation or to present a façade of generosity, there exist an eyebrow-raising number of statements and anecdotes that, when compiled, present a self-damning picture of Stan Lee. For instance, referring to his lackluster creative output between 1945 and 1961 he says, revealingly: “In fact, I was probably the ultimate, quintessential hack” (Riesman, 2021). Over the course of his life, Stan Lee participated in countless interviews, many of which discussed the creative process at Marvel. Stan’s answers and explanations run the gamut from unapologetic declarations of sole authorship to generous acknowledgements of the efforts of folks like Jack Kirby. Whether they are Freudian slips or rare examples of honesty, Lee, on multiple occasions, would make quips similar to the one he made regarding a collaboration with filmmaker Terry Dougas: “He does all the work, I take all the credit…” (Riesman, 2021). At the 1975 San Diego Comic-Con, Lee begins a story this way: “I better watch what I say, ‘cause I never know; Jack may be here. I’m not noted for always telling the truth, but at least people don’t usually catch me at it.” He is referring more to a spotty memory rather than blatant dishonesty, but still. In the introduction to How to Draw Comics the Marvel Way, Stan quips: ‘John Buscema would organize, prepare, and illustrate our book–based on the highly successful course he teaches in his own workshop–and I would do the writing and sneakily steal a disproportionate share of the credit, as is my wont.” Yes, it most certainly was. During an interview with comics veteran Harvey Kurtzman in the late 80s, Stan let fly this doozy: “Just like old times: You do the work and I’ll take the credit!” A still-resentful Kurtzman was not amused. The saying goes: out of the abundance of the heart, the mouth speaks. These few examples of Stan slips, in conjunction with other revealing statements, force us to more serious inquisition.

Time after time, Lee takes passive aggressive swipes at other Marvel creators in his Stan’s Soapbox and Letters columns, usually in response to their legitimate grievances about writer credit (Morrow, 2019). Almost from the get-go, Lee throws Steve Ditko under the bus for any efforts to assert creative rights. After Ditko creates Dr. Strange, Lee felt the need to knock him down a few pegs with these letters column comments: “Steve Ditko is gonna draw him. Sort of a black magic theme. The first story is nothing great, but perhaps we can make something of him–‘twas Steve’s idea, and I figgered we’d give it a chance…” When readers sent letters complaining about Ditko’s art style, Stan made sure to publish them, sometimes responding in ways that added insult to injury: “Steve was just about to send away for a mail-order course in drawing!” After getting a complimentary letter about the plot in one of Ditko’s Spider-man issues, Lee takes credit and then feels the need to include this jab: “… do you hear sensitive Stevey muttering in the background? Something like: ‘So what was the artwork–chicken liver??’” Steve Ditko was not the only victim of Lee’s immature bullying. After Wallace Wood asserts himself and asks for rightful pay and credit for penciling and writing a Daredevil story, Lee adds this blurb to the issue: “Wally Wood has always wanted to try his hand at writing a story as well as drawing it, and Big-Hearted Stan (who wanted a rest anyway) said okay. So what follows next is anybody’s guess. You may like it or not, but you can be sure of this… it’s gonna be different!” After some ensuing conflict, Wood refuses to do the dialogue in the next issue, which leads to Lee pouring gasoline on the fire: “Now that Wally got writing out of his system, he left it to poor Stan to finish next issue. Can he do it?” The next issue continues the pile on: “…Wonderful Wally decided he doesn’t have time to write the conclusion next ish, and he’s forgotten most of the answers we’ll be needing! So, Sorrowful Stan has inherited the job of tying the whole yarn together and finding a way to make it all come out in the wash! … It’s all up to Stan!” (Morrow, 2019). Besides the swipes themselves, another habit of Lee’s jumps out from these examples: his affinity for assigning condescending nicknames to friends and foes alike. At first blush, they seem to be in good fun, but there is often a sharp edge that is most definitely being used purposefully.

Not once, but twice, a young Stan Lee publicly declared himself “God.” Although these were ostensibly meant as gags, they raise a red flag in connection with his personality (Riesman, 2021). The first occurred when Lee was in high school and worked at the school literary magazine. As Lee himself tells it, one day he climbed a ladder and painted “Stan Lee is God” on the ceiling of the magazine classroom. The second story is related by Adele Kurtzman, a secretary during the Atlas/Timely days. As she recounts: “[Once,] he climbed to the top of a filing cabinet in the room next to ours and said, ‘I am God and I want all of you to bow to me!’” (Riesman, 2021). Although it’s the topic for another paper, anecdotes like this led me to a cursory examination of narcissistic personality disorder and, perhaps not surprisingly, Stan Lee checks the most significant symptom boxes: an exaggerated sense of self-importance, requiring constant, excessive admiration, a tendency to exaggerate achievements and talents, a belief in their own superiority, taking advantage of others to get what they want. Underlying these traits is a fragile self-esteem, vulnerable to the slightest criticism (Mayo Clinic, 2021). After hearing and recognizing the validity of the following Robert Hughes quote many years ago, I could not help but think of it in this context: “The greater the artist, greater the doubt. Perfect confidence is granted to the less talented as a consolation prize.”