Stan Lee’s comic characterizations relied on not much more than repetitive formulas and a grab-bag approach to assigning super powers. Lee’s very first comic story introduces a muscle-bound iceman named “Jack Frost.” Abraham Riesman keenly observes: “This comics debut for Stan presaged a running motif in the vast majority of the super-characters he created after his Marvel heyday: a figure based on a weird gimmick that doesn’t quite work and leaves no trace on the cultural psyche” (Riesman, 2021). Well into the 1990s, Stan was still suggesting new characters to the folks at Marvel. One idea was to create a crimefighter based on real-life model, Jackie Tavarez, called Nightcat. Tavarez went so far as to record an album of Nightcat themed songs for the project. Despite her contribution, “…every aspect of the endeavor landed with a thud” (Riesman, 2021). Another pitch was for a superpowered garbageman named Ravage. Legendary Marvel artist/creator Steve Ditko entertained the idea of collaborating on the project, but after reaching a creative stalemate with Lee, it never got off the ground (Riesman, 2021). A number of large-scale projects emerged during the SLM and POW! days that introduced even more characters with stale powers and uninspiring backstories. The vast majority either flopped or never materialized, despite the hype that proceeded them. It would be easy to chalk these casualties up to a fickle entertainment industry, but an honest examination simply uncovers threadbare concepts.Of that time period, it was observed by Marvel film agent Don Kopaloff: “It was like Laurel and Hardy without Laurel.” Stan was there and, yes, he was recognizable, but he was deprived of the human creative force that had powered so much of Marvel’s success: Kirby” (Riesman, 2021). I do not believe it is coincidence that so many of the Marvel characters created in the 1960s are household names, whereas even genuine comics fans would have difficulty composing even a short list of Lee-created characters from all the decades that followed.

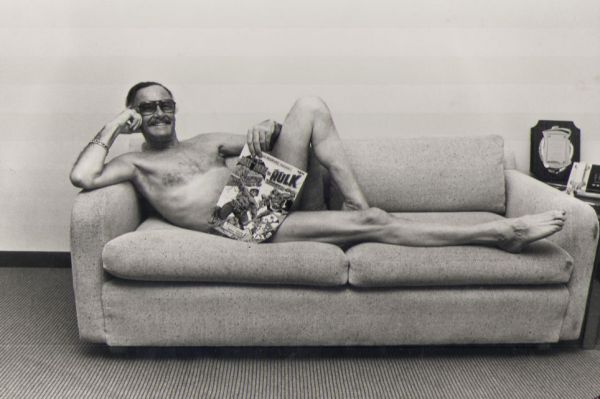

It is hard to ignore recurring motifs that present Stan Lee as a man obsessed with the licentious, or, at the very least, a devoted adherent of the formula: “sex sells,” and its ugly byproduct: the objectification and side-lining of women. Although not emanating from a Puritanical vantage point, it doesn’t escape notice that many of Stan’s creative pitches bordered on sleaze. I don’t believe it’s necessarily a fair point to weigh against inherent creativity, however, the bawdiness seems always to emanate from his own “leering propensities” (Romberger, 2021) and not as an element of a larger conceptual idea. Stripperella may be the most high-profile example. Here is yet another “gimmick” character (a stripper who fights crime) that lacked any hint of thoughtful backstory. Although Pamela Anderson, upon whom the character is based, is said to have hit it off with Lee, she points out one area of disagreement: “Stan wanted nudity. I didn’t” (Riesman, 2021). Some argue, convincingly, that objectifying and side-lining women was not the exception but the rule in Lee’s work (Romberger, 2021). And, despite a progressive Kirby’s best efforts to introduce and develop strong and proactive female characters with agency, Lee would invariably undermine them with truly cringe-inducing dialogue.

Amongst his early days newspaper strip pitches there are examples of stories such as Love of Linda and Li’l Repute that seem to hinge on their main character being physically appealing (Riesman, 2021). A truly disconcerting magazine proposal that partnered Stan with Will Eisner suggested alarming topics like: “Pornography is no longer interesting so what’s next??” and “Shall we legalize rape?” (Riesman, 2021). A comic pitch to Playboy, which is at least an appropriate venue, featured a character named High Priestess Clitanna and included story titles like “Thomas Swift and His Evasive Erection.” This could have gone hand in hand with his idea for magazine called Film International which would have as its focus pornographic movies and was apparently just a vehicle to host “Playboy-esque parties where Stan could be photographed alongside celebrities” (Riesman, 2021). Respected Marvel writer, Chris Claremont, related a story where Stan offered his two cents on a Ms. Marvel drawing he happened upon. Despite an established backstory that would have eschewed the suggestion, Stan offered up this advice: “Ah! Can’t we make her more sexy? Can’t we put her in hot pants and a tight, stylish top?” (Riesman, 2021). Then there was a mid-nineties Lee–Shultz Production idea called Decoy that was described as “A One Hour Erotic Action Series Like None Ever Seen on TV Before.” The main character “is an uninhibited woman–who knows she’s one hot, desirable ‘babe’ and isn’t shy about using her voluptuous body and all her feminine wiles to get what she wants…” (Riesman, 2021). Stan had these suggestions for a kid-oriented fan club (for SLM) called SCUZZLE that needed a shot in the arm: “Just like there’s a ‘Playboy’s Playmate of the Week,’ let’s have a ‘Scuzzle Sweetie of the Week…” and adding “… some features like “Maggie the Model,” “Supermodels from Hell!”, “Melanie’s Modeling School,” “Bikini Betty, the Peach of the Beach,” “Stan’s Bikini Babe of the Week” (Riesman, 2021). And then there was this gem, discovered in Box 53 of the Stan Lee archives: an idea for “a book or magazine entitled Fannies, which would have “Photos of gals’ (+guys’) backsides (candid + posed) (in + out of clothes)” (Riesman, 2021). Again, the ribald nature of these pitches doesn’t, in itself, disqualify them from a discussion of inherent creativity but, when placed alongside a lifetime of diminishing women, we come away with an image of a man more obsessed with tearing down females than building touchstone stories and characters.